Overview

The development of complex open source solutions is generally done by adapting and integrating multiple existing components. The resulting application (or “solution”) may look as a single program from the user point of view, but is in fact a combined work. The different components may be covered by different licences. Are they compatible and legally interoperable?

Determining whether the various licences involved are compatible is important when the aim is to redistribute the application to third parties: under what open source licence should it be distributed? Is this always possible?

The licences for distributing free or open source software (FOSS) are divided in two families: permissive and reciprocal (or "copyleft"). Permissive licences (BSD, MIT, X11, Apache, Zope) are generally compatible and interoperable with most other licences, tolerating to merge, combine or improve the covered code and to re-distribute it under many licences (including non-free or “proprietary”).

At the contrary, the reciprocal licences impose to provide back the source code under the same licence in case of distribution, when the distributed work is a derivative of the covered work. To avoid software appropriation by third parties, many open source projects have adopted reciprocal licensing terms: this is the case of the two Gnu GPLs and the EUPL.

Some licences like the LGPL or the MPL try to compromise between the permissive and reciprocal requirements: covered components (and their specific derivatives) will always keep their primary licence, but the combined application “as a whole” (even if it may be considered globally as a derivative) or its executable binary (a single program from the user point of view) can be distributed under any licence.

Compatibility is the possibility to combine or merge software code covered by several licences and to distribute the combined work. At the contrary, licence incompatibility exists when a program is derivative of components licensed under two different reciprocal licences (for example, the GPLv2, which is still the most used copyleft licence, is not compatible with GPLv3, and vice-versa).

Interoperability is another legal concept originally defined by Directive 91/250/EEC as "the ability to exchange information and mutually to use the information which has been exchanged" (Recital 10).And to implement interoperability, the reproduction of "interfaces" (also defined in as "the parts of the program which provide for interconnection and interaction between elements of software") is authorised as a copyright exception to the author's exclusive rights (possibly formalised in a copyright licence), This is the reason why the EUPL, by application of EU law, is interoperable. This is a major difference with some other reciprocal licences (mainly the GPL v2, GPL v3 and AGPL) where the license steward states that static or dynamic linking extend their copyright.

Dual licensing

A logical incompatibility issue may be resolved through dual licensing: the original licensor (owning full copyright) may provide the same program under two or more licences, even if these licenses are not compatible.

The most frequent cases apply to licensors distributing their work under the “GPL” (without mentioning the version number, or adding "or later"): in such case, recipients can use the work under any of these licences (GPLv2 or GPLv3), which is in practice a dual licensing.

When the licences are mutually incompatible, the risk of dual licensing is the forking of the program in various legally incompatible releases, which even the original licensor will not be able to reunify.

Exception lists

An alternative way to resolve incompatibility issues without the risk of forking is the constitution of an exception list. The advantage is to maintain the licensed component under a single licence including its specific derivatives, while allowing combined derivative works where the component is integrated or merged to be licensed under an alternate licence. The difference with the more permissive LGPL system is that exception lists specify which licence(s) are accepted as secondary licence (not “any” licence).

Exception lists can be implemented at licence level: this is done by the EUPL, where an appendix of “compatible licences” specifies which licences can be used in case of “combined derivative” (when the program is a derivative of both a EUPLed component and another component licensed under a compatible licence).

Exception lists can also (and in addition) be implemented by a specific licensor. This is especially recommended when a licensor distributes a library of components under a copyleft licence (as the GPLv2 or V3) instead of using the more permissive LGPL or MPL (which are generally the most adapted licences for such components). For example, Oracle distributes MySQL component libraries under the GPLv2, but has implemented the “MySQL FOSS Exception List” authorising the distribution of combined derivatives under about 20 other FOSS licences (including the copyleft GPLv3 and the EUPL). Example: http://www.mysql.com/about/legal/licensing/foss-exception/

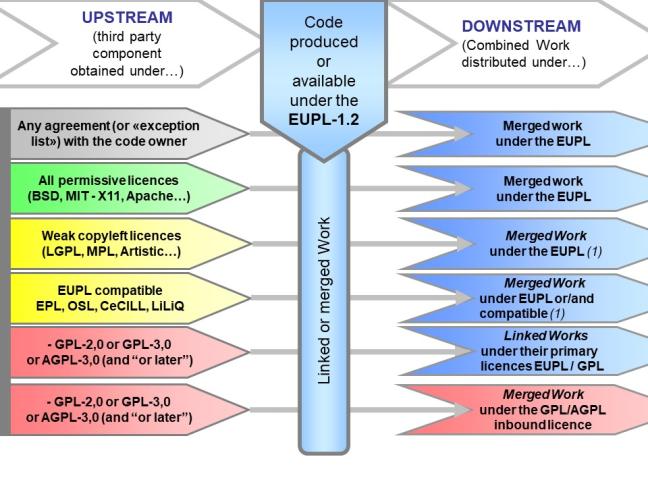

Illustration: the EUPL compatibility

The EUPL upstream (incoming components) and downstream compatibility (distribution of the resulting work) can be illustrated as follows:

For a complete analysis of the EUPL compatibility (with all OSI-approved licences) please refer to the EUPL compatibility matrix. The EUPL v1.2, published in May 2017 (OJ 19/05/2017 L128 p. 59–64 ) has extended the EUPL compatibility to GPLv3, AGPL and other licences. Joinup has developed the Licensing Assistant (JLA) that includes a compatibility checker.

More details on the case of linking

Linking two programs or linking an existing software with your own work does not – at least under European law – produce a derivative or extend the coverage of the linked software licence to your own work. This opinion is based on the Directive 91/250/EEC on the legal protection of computer programs (re-codified in Directive 2009/24/EC). The aim of this Directive is to facilitate interoperability, making possible to connect all components of a computer system, including those of different manufacturers or authors, so that they can work together. Therefore the parts of the programs known as ‘interfaces’, which provide interconnection and interaction between elements of software and hardware may be reproduced by a legitimate licensee without any authorisation of their rightholder (Recitals 10 & 15 of the Directive). This implies that such interfaces escape to the copyleft provision of any licence, open source (like the GPL or EUPL) or proprietary. The technical way of linking for interoperability (static or dynamic) should not make any difference. For this purpose, the Directive (article 6) authorises the legitimate licensee to decompile the licensed program in order to obtain the information necessary to achieve the interoperability. This information can then be reproduced for the purpose of writing the interface. At the time the 1991 directive was written, the open source option was not considered (the concept has been forged later, in 1998): indeed, decompilation targets the case where the legitimate licensee has received the licensed program in object code only. However, it looks obvious that the exception implemented by the Directive could be used also when the licensee has access to the source code: in such case, code needed for interoperability is directly available, without the need for a decompilation. It remains that such an exception to the author's exclusive rights must be strictly limited to the interconnection of independent programs, which is not the case when a specific extension or "add-on" is designed for modifying or extending the functionalities of a third party program and could then be considered as a derivative of this program. The reproduction must be limited to parts that are needed for interoperability and may not be used in a way which prejudices the legitimate interests of the rightholder or which conflicts with a normal exploitation of the third party program.

A question to clarify at early stage

The sooner you examine licence compatibility issues, the better it is. If the intention of the software producer is to distribute the work under a specific licence, it is advised to declare this licence in the specifications (if software developers are contractors, they will be responsible for using new or compatible components) or in a contributor’s agreement (if the software is produced by a FOSS community of developers).